Shoulder Anatomy

The shoulder is a remarkable joint with one of the highest degrees of motion of any joint in the human body.

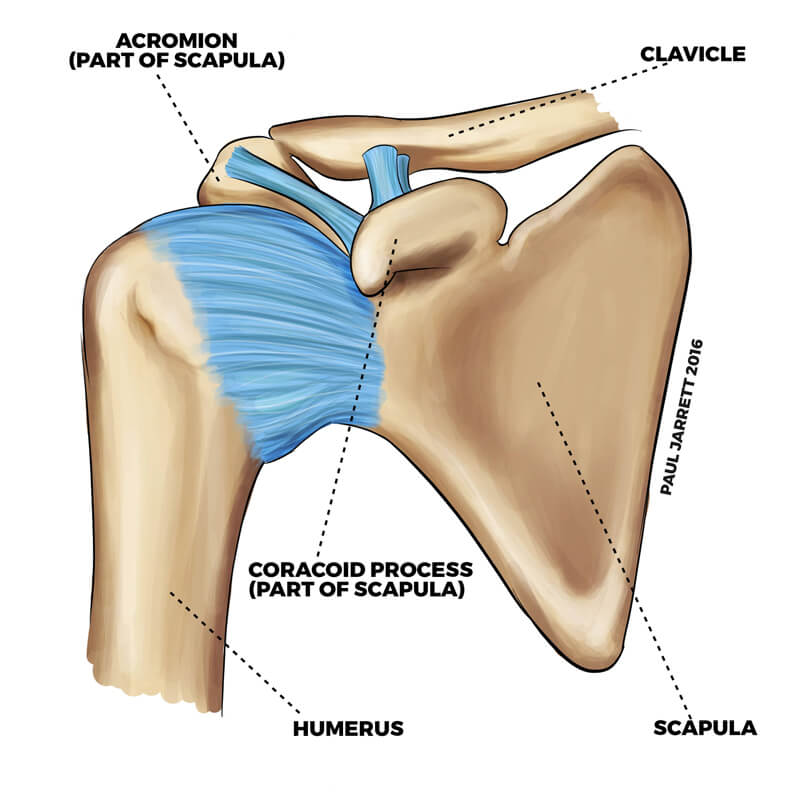

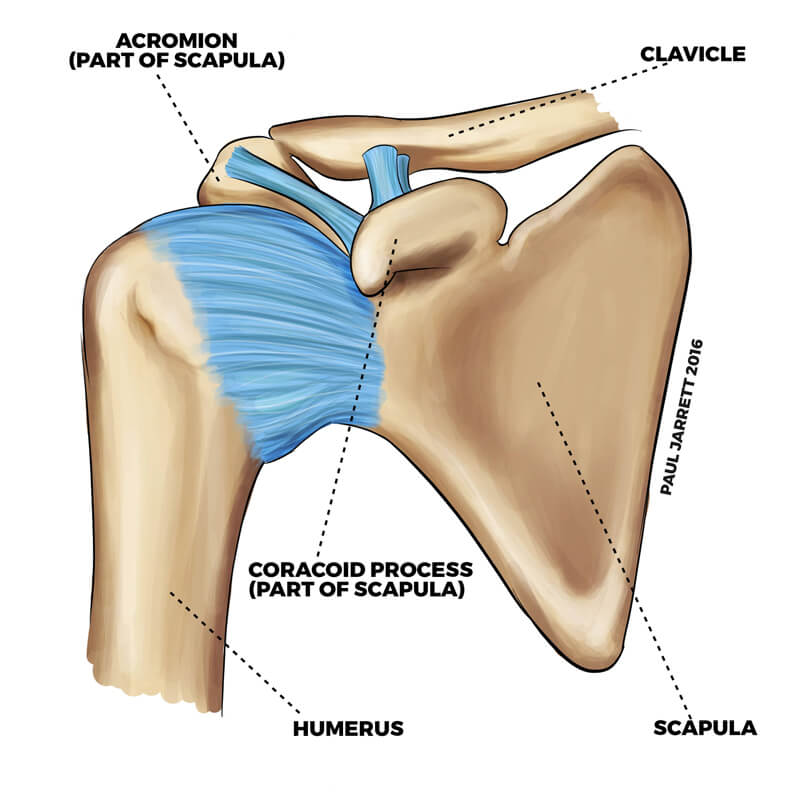

Like most joints in the human body, it consists of multiple structures which work together in a complex manner to produce a strong, stable joint with an extraordinary degree of motion.At the centre of the shoulder lies the shoulder blade (scapula) which has a socket (glenoid) towards its outer aspect. The upper arm bone (humerus) forms a ball shape (humeral head) at the end, which forms a ball-andsocket joint with the glenoid called the gleno-humeral joint which is what most people think of as the shoulder joint.

The collar bone (clavicle) helps suspend your upper limb from your chest. At its outer edge, it is attached to an area of your scapula called the (acromion)

The joint where the clavicle and the acromion of the scapula meet is called the acromioclavicular joint sometimes called the AC joint. The AC joint is upported by ligaments between the acromion and clavicle, and some ligaments from another portion of the scapular called the coronoid process to the under surface of the clavicle.

The AC joint can be damaged during injuries or may become inflamed or worn by disease processes, with both being frequent causes of shoulder problems.

The opposite end of the clavicle is attached to the breastbone (sternum) and forms the joint called the sternoclavicular joint (SC joint).

More about your shoulders

For the shoulder to have such a large degree of motion, the glenoid cavity has to be very shallow. The edge of the glenoid is surrounded by firm cartilage called the labrum, which increases the stability of the shoulder joint by effectively deepening the glenoid cavity. Attached to the labrum and the side of the glenoid is the shoulder capsule. The shoulder capsule is tissue surrounding the gleno-humeral joint which has several discrete thickened areas called ligaments. The capsule normally has sufficient slackness to allow shoulder motion but is present to prevent excessive shoulder movement. Injury to the glenoid, labrum or the capsule can occur during shoulder dislocations and can predispose some patients to the future risk of dislocation or shoulder instability. In a frozen shoulder, the capsule becomes thickened and tightens up causing shoulder stiffness and pain.

There are muscles attached to both surfaces of the scapula which then turn into tendons which attach to the top of the humerus bone. The four muscles are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor at the back of the scapula and subscapularis on the surface of the scapula opposite the chest wall. The tendons of these four muscles blend to form a broad tendon called the rotator cuff tendons. The rotator cuff and its muscles are partially responsible for the movement of the shoulder but more importantly its primary function is to help coordinate the motion of the shoulder, allowing the gleno-humeral joint to be centred and to work well. Poor function, wear, or tearing of the rotator cuff tendons is a common cause of shoulder problems.

There are some other muscles around the shoulder which produce motion and aid the function of the shoulder. If they cease to work properly, this will affect shoulder and upper limb function. These muscles include the; Pectoralis Major which is a fan-shaped muscle that lies between the ribs at the front of your chest and attaches to the top and front of the humerus bone,

Latissimus Dorsi which lies between the back of your chest and runs to the top and front of your humerus, Deltoid which lies between the clavicle and the top of the scapula and drapes over the side of your shoulder inserting into the top of your humerus, positioned somewhat lower than where the rotator cuff tendon inserts into the bone.

The bursa is a fluid-filled sac which assists in shoulder function by reducing the friction between the underlying tendon and the bone of the acromion above. It is possible for the bursa to become swollen inflamed, filled with fluid, or scarred (bursitis) and this is a frequent cause of shoulder symptoms including impingement.

The biceps muscle in your arm has two tendons going into the shoulder region. One tendon called the “short head of biceps” inserts into the coracoid process and the other called the “long head of biceps” inserts into the labrum at the top part of the glenoid. The long head of biceps exits the shoulder by passing through a pulley system in the rotator cuff tendons and travels for a short length down a groove in the humerus covered by a ligament. The long head of biceps can become torn where it inserts into the labrum or inflamed, worn, or torn where it travels along the groove, causing shoulder pain, weakness or stiffness.

There is an area beneath the acromion and above the top of the humerus called the subacromial space. There is a ligament called the coracoacromial ligament which stretches between the front of the acromion and a prominence of the scapula which is called the coracoid process. In the subacromial space sits the rotator cuff tendons, and above the tendons, a structure called the subacromial bursa.